Beneath the waves and buried under centuries of sediment lie the remnants of once-thriving harbor cities that shaped ancient civilizations and maritime trade routes.

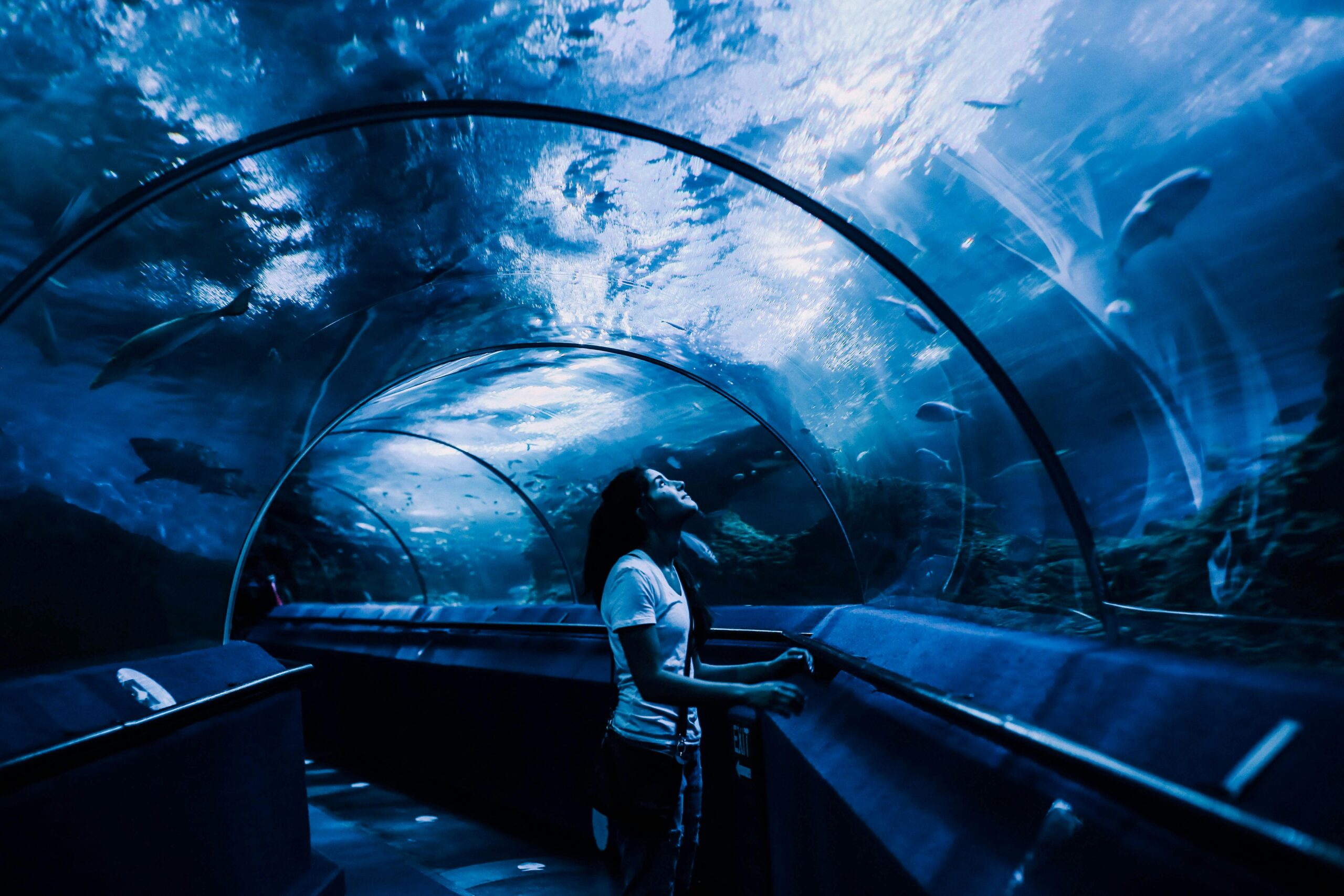

The story of humanity’s relationship with the sea is written in the submerged stones of forgotten ports, harbors, and coastal settlements. These lost cities represent not just architectural achievements, but the economic, cultural, and technological pinnacles of ancient societies that depended on maritime connections for survival and prosperity.

From the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, archaeologists and marine researchers continue to discover evidence of sophisticated port infrastructure that challenges our understanding of ancient engineering and navigation. These underwater archaeological sites offer unprecedented glimpses into daily life, trade networks, and the environmental factors that led to their eventual abandonment.

🌊 The Sunken Legacy of Pavlopetri: Europe’s Oldest Submerged City

Off the southern coast of Laconia in Greece lies Pavlopetri, a Bronze Age harbor city that dates back approximately 5,000 years. This remarkable archaeological site represents one of the oldest planned cities ever discovered, complete with streets, buildings, and harbor facilities that reveal sophisticated urban planning.

Pavlopetri sank beneath the waves around 1000 BCE, likely due to a combination of earthquakes and rising sea levels. The preservation of this ancient port is exceptional, with archaeologists mapping at least 15 separate buildings, courtyards, streets, chamber tombs, and a complex water management system that serviced the harbor operations.

The harbor infrastructure at Pavlopetri demonstrates advanced understanding of maritime logistics. Stone anchors, cargo handling areas, and protective breakwaters indicate that this was not merely a fishing village but a significant trading hub connecting the Aegean world with broader Mediterranean networks.

Thonis-Heracleion: Egypt’s Gateway to the Mediterranean World

For centuries, Thonis-Heracleion existed only in ancient texts and fragmentary references by Greek historians. Then, in 2000, French archaeologist Franck Goddio discovered the lost city submerged in Abu Qir Bay near Alexandria, Egypt. This revelation transformed our understanding of ancient Egyptian maritime commerce.

Thonis-Heracleion served as Egypt’s main international trading port before the foundation of Alexandria in 331 BCE. The city controlled all maritime traffic entering Egypt from the Mediterranean, making it an essential customs checkpoint and religious center. Massive statues, temple remains, and harbor installations recovered from the seafloor paint a picture of a cosmopolitan metropolis where Egyptian, Greek, and Phoenician cultures intersected.

The harbor facilities included massive limestone blocks that formed quays and harbor walls, along with an intricate network of canals and basins that allowed ships of various sizes to dock safely. Wooden stakes and stone anchors still mark ancient mooring points where merchant vessels once tied up to unload precious cargoes from across the known world.

Archaeological Treasures from the Deep ⚓

Excavations at Thonis-Heracleion have yielded extraordinary artifacts that illuminate ancient maritime trade practices. Gold coins, bronze vessels, pottery from distant lands, and religious offerings demonstrate the city’s role as both a commercial and spiritual center. Perhaps most significantly, inscribed stelae discovered at the site have helped archaeologists precisely identify the location and understand the administrative functions of this crucial port.

The Drowned Harbors of the Indus Valley Civilization

While less visually dramatic than Mediterranean discoveries, the investigation of ancient Harappan ports along the northwestern coast of India and Pakistan has revolutionized our understanding of Bronze Age maritime trade in the Indian Ocean. Lothal, located in present-day Gujarat, features one of the world’s earliest known dock systems, dating to approximately 2400 BCE.

The Lothal dockyard was an engineering marvel of its time, measuring 214 meters long and 36 meters wide. This massive basin connected to an ancient course of the Sabarmati River through a sophisticated inlet-outlet system that managed tidal flows. The dock could accommodate multiple large vessels simultaneously, suggesting significant maritime traffic between the Indus Valley and Mesopotamian civilizations.

Recent underwater surveys along the Cambay Gulf have identified several submerged structures that may represent additional Harappan coastal settlements. These potential sites, now underwater due to post-glacial sea level rise, could provide crucial information about the maritime capabilities and trade networks of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Ancient Caesarea: Rome’s Engineering Triumph Against the Sea 🏛️

Herod the Great’s construction of Caesarea Maritima between 22 and 10 BCE represents one of antiquity’s most ambitious harbor engineering projects. Built on a relatively inhospitable stretch of the Levantine coast with no natural harbor, Caesarea required revolutionary construction techniques that pushed Roman engineering to its limits.

The harbor featured massive breakwaters constructed using hydraulic concrete that hardened underwater—an innovation that wouldn’t be matched until modern times. These breakwaters created a protected artificial harbor covering approximately 40 acres, making it one of the largest ports in the Roman Mediterranean.

Today, much of ancient Caesarea’s harbor lies underwater, victim to gradual subsidence, sediment accumulation, and deterioration of the concrete foundations. Underwater archaeological excavations have revealed the sophisticated design elements including warehouses, cargo handling facilities, and the remains of the lighthouse that once guided ships to safety.

The Technology Behind Submerged Archaeology

Modern exploration of lost harbor cities relies on cutting-edge technology that allows researchers to see through murky waters and penetrate sediment without extensive excavation. Side-scan sonar creates detailed acoustic images of the seafloor, while magnetometry detects ferrous materials and buried structures. Sub-bottom profilers reveal layers of sediment and objects buried beneath the seabed.

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) equipped with high-definition cameras allow archaeologists to conduct initial surveys and detailed inspections without the time limitations imposed on human divers. Photogrammetry techniques create three-dimensional models from hundreds of overlapping photographs, preserving digital records of submerged archaeological sites.

Dwarka: Between Mythology and Archaeological Reality

Off the coast of Gujarat, India, underwater investigations have identified stone structures, walls, and artifacts that some researchers associate with the legendary city of Dwarka, said to be the kingdom of Lord Krishna in Hindu mythology. While the connection to mythological accounts remains controversial, the archaeological evidence confirms significant ancient maritime settlement in this area.

Marine archaeological surveys have documented stone anchors, pottery, and structural remains extending along the seabed. Carbon dating of some artifacts suggests human activity in this area dating back several thousand years. The site demonstrates that the region supported substantial coastal populations engaged in maritime activities long before the current historical period.

The investigation of submerged sites like Dwarka illustrates the complex relationship between mythology, oral tradition, and archaeological evidence. While not every legendary city will have a historical counterpart, ancient stories sometimes preserve kernels of truth about real places and events that were later embellished through centuries of retelling.

Port Royal: The “Wickedest City” Preserved by Disaster ☠️

While not ancient in the classical sense, Port Royal, Jamaica, provides a unique case study in harbor city preservation. On June 7, 1692, a massive earthquake and resulting tsunami caused approximately two-thirds of this thriving Caribbean port to slide into the sea, creating a time capsule of late 17th-century maritime life.

Port Royal served as the commercial hub of English Jamaica and a notorious haven for privateers and pirates. Its sudden destruction and submersion preserved buildings, ships, and artifacts in remarkable condition. Archaeological excavations have recovered everything from intact buildings to pocket watches stopped at the moment of the earthquake.

The site offers archaeologists insights into colonial-era shipbuilding, maritime trade, daily life, and the cultural mixing that characterized Caribbean port cities. The preservation conditions are exceptional because the rapid burial in sediment protected organic materials that would normally deteriorate in underwater environments.

Climate Change and the Future of Coastal Archaeological Sites 🌡️

Rising sea levels threaten not only modern coastal communities but also shallow-water archaeological sites that have survived for millennia. Increased wave action, changing water chemistry, and accelerated erosion endanger submerged harbors and shipwrecks that constitute our maritime cultural heritage.

Paradoxically, climate change may also reveal previously inaccessible sites. Retreating glaciers expose settlements abandoned during ancient cold periods, while shifting coastlines reveal structures previously buried under beaches and coastal sediments. This creates both opportunities and urgent challenges for maritime archaeologists.

The race to document threatened sites has accelerated international cooperation in underwater archaeology. UNESCO’s Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage provides a framework for preserving these irreplaceable resources, though enforcement remains challenging in international waters.

Lessons from Lost Harbors for Modern Cities

Ancient harbor cities offer valuable lessons for contemporary coastal urban planning. Many of these settlements were abandoned due to environmental changes that their inhabitants couldn’t prevent or adapt to: earthquakes, tsunamis, sea level changes, and shifting river courses all claimed thriving ports.

Modern coastal cities face similar vulnerabilities amplified by climate change. The archaeological record shows that even sophisticated ancient civilizations with generations of maritime experience could not always protect their harbor infrastructure from natural forces. This historical perspective informs current debates about coastal adaptation, resilient infrastructure, and the long-term sustainability of settlements in geologically or climatologically vulnerable locations.

The Economic Networks That Connected Ancient Ports

Lost harbor cities weren’t isolated entities but nodes in complex trade networks spanning thousands of miles. Ceramic evidence from Thonis-Heracleion includes pottery from Greece, Phoenicia, Cyprus, and the Aegean islands. Lothal yielded beads and seals that match materials found in Mesopotamian sites, confirming direct or indirect trade connections across the Arabian Sea.

These maritime networks facilitated not just commodity exchange but also the transmission of ideas, technologies, artistic styles, and religious practices. Port cities served as cosmopolitan mixing zones where different cultures interacted, creating hybrid traditions and fostering innovation.

Understanding these ancient trade networks helps archaeologists trace the distribution of materials, the movement of people, and the diffusion of cultural practices. It also reveals economic resilience and adaptability—when one port declined, trade routes shifted to alternatives, demonstrating the flexibility of ancient commercial systems.

Preserving Our Submerged Heritage for Future Generations 📚

The exploration and preservation of lost harbor cities faces numerous challenges. Underwater sites are vulnerable to looting, trawling damage, development projects, and natural deterioration. Unlike terrestrial archaeological sites, submerged locations are difficult to secure and monitor.

International cooperation has produced some success stories. The establishment of underwater archaeological parks, like those at Caesarea and Baiae in Italy, allows controlled public access while protecting fragile remains. These sites combine conservation with education, letting visitors experience maritime heritage through guided diving tours and underwater trails.

Digital preservation technologies offer new approaches to conservation. High-resolution 3D models, virtual reality reconstructions, and online databases make these sites accessible to researchers and the public worldwide without physical disturbance. As scanning technologies improve, comprehensive digital archives may become the primary means of preserving information from the most threatened sites.

Uncharted Waters: The Future of Harbor City Archaeology 🔍

Recent advances in technology and methodology suggest that many more lost harbor cities await discovery. Satellite imagery analysis, particularly using synthetic aperture radar and multispectral imaging, can detect subtle seafloor features that indicate human-made structures. Artificial intelligence algorithms now analyze sonar data more efficiently than human researchers, identifying patterns that warrant closer investigation.

Citizen science initiatives are expanding the reach of maritime archaeology. Divers, fishermen, and coastal residents contribute observations and photographs that help researchers identify potential sites. Online platforms allow volunteers to analyze satellite imagery and sonar data, multiplying the human resources available for initial site detection.

The coming decades will likely yield spectacular discoveries as technology improves and researchers explore previously inaccessible areas. Deep-water harbor facilities, if they exist, remain almost entirely unexplored due to the technical challenges of working at extreme depths. As deep-sea exploration technology advances, our map of ancient maritime civilization may expand significantly.

The lost harbor cities of ancient civilizations represent far more than archaeological curiosities. They are windows into the maritime foundations of human civilization, reminding us that connectivity through sea routes has shaped societies for millennia. These submerged sites preserve evidence of human ingenuity, adaptation, and the eternal relationship between humanity and the oceans that both connect and challenge us. As we face our own era of environmental change and coastal challenges, the lessons from these forgotten shores become increasingly relevant, offering both cautionary tales and inspiration for resilient coastal communities.

Toni Santos is a visual storyteller and archival artist whose work dives deep into the submerged narratives of underwater archaeology. Through a lens tuned to forgotten depths, Toni explores the silent poetry of lost worlds beneath the waves — where history sleeps in salt and sediment.

Guided by a fascination with sunken relics, ancient ports, and shipwrecked civilizations, Toni’s creative journey flows through coral-covered amphorae, eroded coins, and barnacle-encrusted artifacts. Each piece he creates or curates is a visual meditation on the passage of time — a dialogue between what is buried and what still speaks.

Blending design, storytelling, and historical interpretation, Toni brings to the surface the aesthetics of maritime memory. His work captures the textures of decay and preservation, revealing beauty in rust, ruin, and ruin’s resilience. Through his artistry, he reanimates the traces of vanished cultures that now rest on ocean floors, lost to maps but not to meaning.

As the voice behind Vizovex, Toni shares curated visuals, thoughtful essays, and reconstructed impressions of archaeological findings beneath the sea. He invites others to see underwater ruins not as remnants, but as thresholds to wonder — where history is softened by water, yet sharpened by myth.

His work is a tribute to:

The mystery of civilizations claimed by the sea

The haunting elegance of artifacts lost to time

The silent dialogue between water, memory, and stone

Whether you’re drawn to ancient maritime empires, forgotten coastal rituals, or the melancholic beauty of sunken ships, Toni welcomes you to descend into a space where the past is submerged but never silenced — one relic, one current, one discovery at a time.