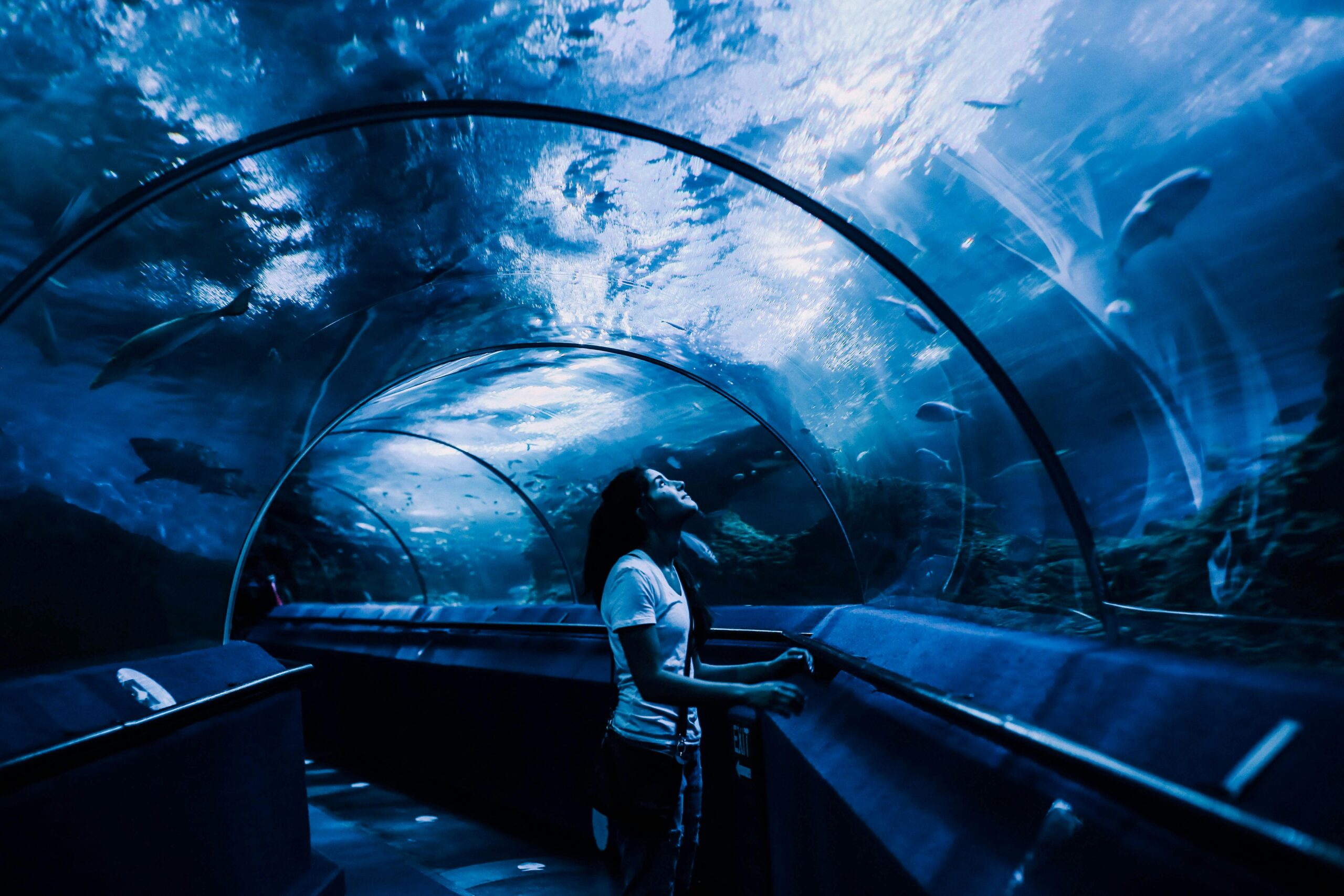

The ocean floor harbors extraordinary secrets of preservation, where organic materials persist for centuries defying conventional expectations of decay and demonstrating remarkable resilience beneath the waves.

🌊 The Paradox of Underwater Preservation

When we think about organic materials, we typically associate them with fragility and rapid decomposition. Yet beneath the ocean’s surface, a completely different story unfolds. The marine environment, often perceived as harsh and corrosive, actually provides unique conditions that allow organic materials to survive far longer than their terrestrial counterparts. This phenomenon challenges our understanding of material degradation and opens fascinating windows into history, archaeology, and material science.

The preservation of organic materials underwater depends on a complex interplay of factors including oxygen levels, temperature, salinity, sediment composition, and microbial activity. In many underwater environments, particularly in deep, cold waters or within anaerobic sediments, organic materials can remain remarkably intact for hundreds or even thousands of years.

The Science Behind Underwater Resilience

Understanding why organic materials survive underwater requires examining the fundamental processes of decomposition. On land, organic matter breaks down rapidly through oxidation, exposure to variable temperatures, UV radiation, and the action of diverse decomposer organisms. Water environments, however, create barriers to many of these degradative forces.

Oxygen Deprivation: Nature’s Preservation Chamber

One of the most critical factors in underwater preservation is the reduced availability of oxygen. In many marine sediments and deep-water environments, oxygen levels drop significantly or disappear entirely, creating anaerobic conditions. Without oxygen, aerobic bacteria—the primary agents of organic decomposition—cannot function effectively. This oxygen limitation dramatically slows the breakdown of wood, textiles, leather, and even human remains.

Shipwrecks buried in sediment exemplify this phenomenon perfectly. Wooden vessels that would decompose within decades on land can survive for centuries when covered by protective layers of sand or mud that exclude oxygen. The famous Mary Rose, a Tudor warship that sank in 1545, retained much of its wooden structure precisely because it became partially buried in sediment that created anaerobic conditions.

Temperature Stability and Cold Water Benefits

Temperature plays another crucial role in preservation. Cold water environments significantly slow chemical reactions and biological processes. The deep ocean, with temperatures hovering near freezing, acts almost like a natural refrigerator. Metabolic rates of decomposer organisms decrease dramatically in cold conditions, extending the lifespan of organic materials exponentially.

Arctic and Antarctic waters demonstrate this effect most dramatically, where organic materials can remain in near-perfect condition for millennia. Researchers have discovered remarkably preserved organic artifacts from ancient cultures in these regions, offering unprecedented insights into historical ways of life.

📚 Historical Treasures Revealed by the Sea

The ocean’s preservation capabilities have gifted archaeology and history with invaluable artifacts that would have vanished completely on land. These underwater time capsules provide direct connections to past civilizations and events.

Ancient Shipwrecks as Cultural Archives

Shipwrecks represent some of the most complete archaeological sites available to researchers. Unlike land-based settlements that experience continuous disturbance, a shipwreck creates a sealed time capsule of a specific moment. Organic materials aboard these vessels—from rope and sails to food stores and personal belongings—often survive in conditions that allow detailed study.

The Vasa, a Swedish warship that sank in 1628 and was raised in 1961, retained over 95% of its original wood along with thousands of artifacts including textiles, rope, and leather goods. This extraordinary preservation was due to the cold, brackish waters of Stockholm harbor and the ship’s rapid burial in soft mud.

Submerged Settlements and Lost Cities

Rising sea levels and coastal subsidence have submerged numerous ancient settlements, preserving organic architectural elements and artifacts that would have disintegrated on land. Sites in the Mediterranean, Black Sea, and elsewhere have yielded wooden building materials, organic-based adhesives, and plant-based artifacts that provide unprecedented detail about ancient construction techniques and daily life.

The Black Sea, with its unique water chemistry featuring an anoxic deep layer, has become famous for exceptional preservation. Researchers have discovered shipwrecks with intact masts, rigging, and even carved decorative elements that look remarkably fresh despite being over two thousand years old.

🔬 Material-Specific Survival Strategies

Different organic materials respond to underwater environments in distinct ways, with some showing remarkable resilience while others remain vulnerable to specific degradation processes.

Wood: The Unexpected Survivor

Wood represents one of the most successfully preserved organic materials in marine environments. When protected from wood-boring organisms and maintained in anaerobic conditions, wooden structures can survive indefinitely. The cellular structure of wood remains intact, though waterlogged wood becomes saturated and loses much of its original strength.

Different wood species show varying resistance to marine conditions. Dense hardwoods like oak generally outlast softer woods. The presence of natural preservatives like tannins also enhances longevity. Interestingly, shipbuilders historically selected wood species partly based on their known durability in marine environments.

Textiles and Fibers

Natural textiles—cotton, linen, wool, and silk—typically decompose rapidly in most environments, but underwater conditions can preserve them surprisingly well. Anaerobic sediments provide the best preservation, protecting textile fibers from both biological and chemical degradation.

Archaeological excavations of shipwrecks have recovered clothing, sails, and rope that retain identifiable weave patterns and sometimes even original colors. These textile finds provide invaluable information about historical manufacturing techniques, trade patterns, and fashion.

Leather and Skin Products

Leather goods often survive well underwater due to the tanning process that stabilized the organic material during manufacturing. Shoes, belts, book bindings, and even leather bottles have been recovered from shipwrecks in recognizable condition. The natural preservatives used in historical tanning processes—typically plant tannins—continue to protect the material even underwater.

🌿 The Microbial Dimension

While reduced oxygen and cold temperatures inhibit many decomposers, underwater environments host specialized microbial communities that interact with organic materials in complex ways. Understanding these microscopic relationships helps explain both preservation and degradation patterns.

Anaerobic Bacteria: Friend or Foe?

Anaerobic bacteria dominate oxygen-depleted underwater environments, but they work much more slowly than their aerobic counterparts. Some anaerobic species can break down organic materials, but the process occurs at a fraction of the rate seen in oxygen-rich environments. This slower metabolism contributes significantly to extended preservation times.

Certain anaerobic conditions actually create chemical environments that actively inhibit decomposition. Sulfate-reducing bacteria in marine sediments produce hydrogen sulfide, which can have preservative effects on some organic materials while corroding metals—creating the interesting situation where organic materials outlast metal components on the same shipwreck.

Biofilm Formation and Protection

Organic materials underwater often become covered with biofilms—complex communities of microorganisms embedded in protective matrices. While biofilms can contribute to degradation, they can also create protective barriers that shield underlying materials from more aggressive decomposers or chemical processes. This dual role makes biofilms a fascinating subject of study in marine preservation.

⚓ Modern Applications and Lessons

The resilience of organic materials underwater has inspired numerous practical applications in modern technology, conservation, and sustainable design.

Conservation Science Advances

Understanding natural preservation mechanisms has revolutionized conservation approaches for waterlogged artifacts. Conservators now use techniques that work with, rather than against, the changes that occurred during underwater burial. Polyethylene glycol treatment for waterlogged wood, for example, replaces water in the cellular structure while maintaining dimensional stability—a technique developed directly from studying naturally preserved specimens.

Biomimicry in Material Design

Engineers and material scientists study naturally resilient organic materials to develop improved synthetic materials. The way certain woods resist marine borers has inspired anti-fouling coatings. The flexibility of waterlogged yet intact ancient rope has informed modern composite fiber development. Nature’s preservation strategies continue to offer lessons for creating durable, sustainable materials.

Environmental Monitoring

Preserved organic materials in marine sediments serve as environmental archives, recording historical ocean conditions, climate patterns, and ecological changes. Researchers analyze ancient wood, plant remains, and other organic materials to reconstruct past environments and understand long-term climate trends. This information becomes increasingly valuable as we face modern environmental challenges.

🌍 Threats to Underwater Preservation

Despite the ocean’s preservation capabilities, underwater organic materials face increasing threats from human activities and environmental changes.

Ocean Acidification and Chemistry Changes

Rising carbon dioxide levels are acidifying oceans worldwide, altering the chemical conditions that have preserved materials for centuries. Changing pH levels can accelerate degradation processes and affect microbial communities that mediate preservation. Sites that remained stable for millennia may face accelerated deterioration in coming decades.

Temperature Increases

Global warming affects not just surface waters but deep ocean temperatures as well. Even modest temperature increases can significantly accelerate biological and chemical processes that break down organic materials. Shipwrecks and archaeological sites in warming waters may deteriorate rapidly after surviving centuries in stable cold conditions.

Physical Disturbance

Bottom trawling, dredging, cable laying, and other seabed activities physically disturb sediments that protect organic materials. Exposing previously buried artifacts to oxygen-rich water initiates rapid deterioration. The expansion of offshore development threatens numerous underwater cultural heritage sites.

💡 The Future of Underwater Organic Preservation

As we deepen our understanding of how organic materials survive underwater, new possibilities emerge for both protecting existing sites and applying these principles more broadly.

Advanced Monitoring Technologies

Researchers are developing sophisticated monitoring systems to track the condition of underwater archaeological sites and organic materials. Sensors measure oxygen levels, temperature, pH, and microbial activity, providing early warning of changing conditions that might threaten preservation. Autonomous underwater vehicles equipped with imaging systems allow regular inspection without physical disturbance.

In Situ Preservation Strategies

Rather than excavating fragile underwater sites, archaeologists increasingly favor in situ preservation—protecting materials in their underwater environment. This approach recognizes that the ocean itself often provides better preservation than any museum environment. Protective measures include sediment reburial, exclusion zones, and artificial reef structures that enhance natural preservation processes.

International Cooperation and Protection

Growing recognition of underwater cultural heritage’s value has spurred international agreements like the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage. These frameworks promote responsible management, scientific research, and protection of submerged sites containing precious organic materials and other artifacts.

🔍 Surprising Discoveries Continue

Modern exploration technology continues to reveal extraordinary examples of organic material preservation underwater. Each discovery refines our understanding and occasionally challenges existing theories.

Recent finds include incredibly preserved Viking ships in Scandinavian waters, Bronze Age settlements with wooden structures still standing beneath Mediterranean waves, and ancient forests submerged by sea-level rise with trees so well preserved they’re commercially harvested for specialty lumber. These discoveries remind us that the ocean conceals countless time capsules waiting to share their stories.

The human dimension of these discoveries resonates powerfully. Personal items preserved underwater—a sailor’s leather shoe, a merchant’s textile samples, wooden toys from a family’s belongings—create immediate, emotional connections across centuries. These organic materials don’t just inform our understanding of the past; they make history tangibly human.

Rethinking Material Impermanence

The remarkable survival of organic materials underwater challenges assumptions about impermanence and fragility. While we often think of stone and metal as durable and organic materials as ephemeral, underwater environments invert this relationship. Ancient wood outlasts iron. Textiles survive when bronze corrodes away. This reversal prompts broader reflection on preservation, value, and our relationship with materials.

Understanding underwater preservation also offers perspective on sustainability and material choices. Modern synthetic materials were developed partly because natural materials seemed too fragile and impermanent. Yet organic materials, given appropriate conditions, can outlast many plastics while remaining environmentally benign. This insight may influence future material science toward bio-based solutions that work with natural processes rather than against them.

The story of organic materials beneath the waves ultimately reveals nature’s remarkable capacity for preservation when conditions align. Cold temperatures, oxygen deprivation, protective sediments, and stable chemistry combine to create natural archives more effective than any museum storage. These underwater time capsules preserve not just objects but moments—capturing technology, culture, and human experience with extraordinary fidelity. As we face environmental changes that threaten these preservation processes, understanding and protecting these hidden reservoirs of resilience becomes increasingly urgent, ensuring future generations can continue discovering and learning from the organic treasures that defy time beneath the waves.

Toni Santos is a visual storyteller and archival artist whose work dives deep into the submerged narratives of underwater archaeology. Through a lens tuned to forgotten depths, Toni explores the silent poetry of lost worlds beneath the waves — where history sleeps in salt and sediment.

Guided by a fascination with sunken relics, ancient ports, and shipwrecked civilizations, Toni’s creative journey flows through coral-covered amphorae, eroded coins, and barnacle-encrusted artifacts. Each piece he creates or curates is a visual meditation on the passage of time — a dialogue between what is buried and what still speaks.

Blending design, storytelling, and historical interpretation, Toni brings to the surface the aesthetics of maritime memory. His work captures the textures of decay and preservation, revealing beauty in rust, ruin, and ruin’s resilience. Through his artistry, he reanimates the traces of vanished cultures that now rest on ocean floors, lost to maps but not to meaning.

As the voice behind Vizovex, Toni shares curated visuals, thoughtful essays, and reconstructed impressions of archaeological findings beneath the sea. He invites others to see underwater ruins not as remnants, but as thresholds to wonder — where history is softened by water, yet sharpened by myth.

His work is a tribute to:

The mystery of civilizations claimed by the sea

The haunting elegance of artifacts lost to time

The silent dialogue between water, memory, and stone

Whether you’re drawn to ancient maritime empires, forgotten coastal rituals, or the melancholic beauty of sunken ships, Toni welcomes you to descend into a space where the past is submerged but never silenced — one relic, one current, one discovery at a time.